AFRICAN POETRY AS COMPASSIONATE INQUIRY

Feb 9, 2026

Venue: Kenya National Theatre.

Date: 23 September 2025.

Facilitators: Noosim Naimasiah & Marley

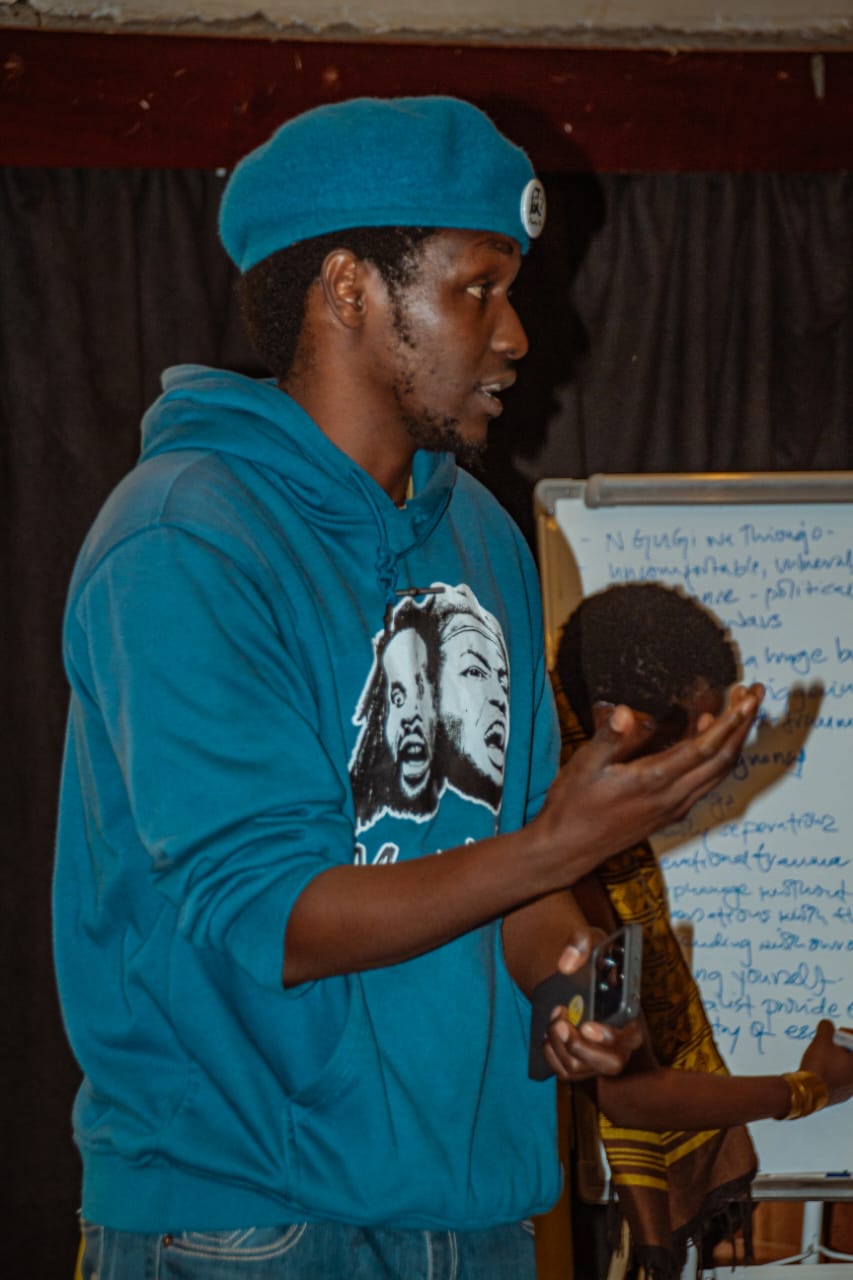

Guest Teacher: Dorphan (Griot and Spoken Word Artist)

Comrades in song.

The master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house’

-Audre Lorde

1. PURPOSE AND FRAMING OF THE GATHERING.

The first African Communities of Healing Praxis session was convened as a collective inquiry into African ways of understanding healing as communal, political, spiritual, and ecological. The gathering set out to challenge individualized, clinical, and depoliticized models of mental health, and to re‑center African epistemologies rooted in ancestry, land, ritual, and collective care.

The session opened with revolutionary songs, grounding participants in shared memory and struggle. Healing was framed not as a private journey but as a political necessity for sustaining movements, relationships, and life itself.

2. NAMING, LINEAGE, AND THE POLITICS OF IDENTITY.

A central thread of the session was the politics of naming and genealogy. Participants reflected on the loss of lineage through colonialism, displacement, patriarchy, family separation, and violence. Naming was discussed as science and as a technology of belonging and healing.

Stories emerged around lost family lines, alienation from ancestral land, and the pain of not knowing one’s origins. Others shared how names, seasons of birth, and ancestral circumstances once structured identity and protection, and how colonial registries, Christianity, and urbanization disrupted these systems.

The act of remembering, tracing family trees, reclaiming African names, and honoring motherlines was perceived simultneously as restorative justice and as resistance to erasure. Participants affirmed that we are not broken individuals but carriers of interrupted lineages seeking reconnection.

Comrade Marley on naming and ancestral knowledge. Comrade Noosim on African Healing.

3. FAMILY, TRAUMA, AND PATRIARCHY

The gathering held conversations about family as both a site of care and harm. Participants spoke openly about generational trauma, orphan hood, abandonment, domestic violence, teenage motherhood, and fractured kinship structures.

Patriarchy was named as a system that harms everyone including women, men, and queer people and producing silence, emotional repression, and distorted notions of responsibility and sacrifice. Father wounds, mother wounds, and the burden placed on families under capitalism and religion were recurring themes.

Participants reflected on how trauma manifests as depression, addiction, anxiety, panic attacks, suicidal ideation, and relational breakdowns. Healing was framed as impossible without confronting these collective wounds and without building communities capable of holding pain without shame.

Comrades Kanare and Mwana.

4. POETRY, ORALITY, AND EMOTIONAL TRUTH

Dorphan’s poetry served as a catalytic force throughout the session. His spoken word performances opened space for vulnerability, memory, and political reflection, allowing participants to access emotions often silenced in activist spaces.

Poetry was affirmed as ancestral medicine and also as a method of telling truth, releasing grief, and making sense of lived contradictions. Many participants shared that the poems allowed them to name pain they had long carried without language.

Dorphan’s poem “Mum aliishia” traced maternal loss, abandonment, and survival, opening a collective discussion on mother-wounds, memory, and grief.

5. EMOTIONAL HEALING AND THE BODY.

The body was consistently named as an archive of memory. Participants spoke about being taught not to cry, to suppress emotion, and to carry pain silently, particularly men. Crying, trembling, and collective tears were reclaimed as necessary acts of healing.

African practices of healing through song, dance, drumming, breath, and collective movement were emphasized. The body was understood as remembering what the mind forgets, and dance as a way ancestors move through us.

Touch emerged as a sensitive but crucial topic: whose touch is safe, how trauma distorts intimacy, and how ritualized, consensual touch can restore trust. Healing was described as learning to inhabit the body again without fear.

6. CEREMONY, RITUAL, AND PRAYER

Participants reflected deeply on the loss of ceremony and the need for intentional ritual. Prayer was re‑imagined beyond colonial Christianity as movement, silence, planting, laughter, breath, and also as music.

Silence was reclaimed as prayer rather than absence. The group discussed the shame imposed on African spiritual practices through colonial law, Christianization, and violence against traditional healers. Relearning how to speak to ancestors without fear was seen as essential to collective healing

Comrades Maryanne and Zangi discussing.

. The master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house’

-Audre Lorde

7. MEMORY AND ANCESTRAL PRESENCE.

Healing was repeatedly described as remembering. Memory lives in smell, sound, taste, and sensation - the smell of soil after rain, the sound of mourning songs, the rhythm of drums.

Participants affirmed that ancestors are not silent or distant but present in land, bodies, weather, and dreams. Remembering circles, storytelling, and listening practices were proposed as ways of restoring memory interrupted by trauma and displacement.

Listening itself was named as a revolutionary act; listening without fixing, without hierarchy, and without urgency.

Comrades Maryanne and Gera join in a song.

8. LAND, ECOLOGY, AND COLLECTIVE CARE

Land was described as therapist, archive, ancestor, and mirror. Participants connected colonial land dispossession to psychological displacement, homelessness, migration, and loss of belonging.

Healing was framed as everyday practice: cooking together, eating together, planting, cleaning, and caring for one another. Food rituals, ancestral meals, seed‑saving, and indigenous agriculture were discussed as sites of memory and resistance.

Environmental destruction including pollution, mining, climate crisis was percieved as spiritual and psychological violence. Healing the land and healing people were described as inseparable processes.

9. AFRICAN PEDAGOGY AND KNOWLEDGE CREATION

The session emphasized healing as both practice and research. Knowledge was generated through storytelling, movement, collective inquiry, and lived experience rather than abstraction alone.

Participants called for the creation of African healing curricula, manuals, and archives grounded in indigenous psychology, herbal knowledge, and spiritual science. Everyone present was held by the programme as both teacher and learner, healer and healed.

10. THE ACTIVIST BODY, REST, AND PLEASURE.

Activist fatigue, martyrdom, and guilt around rest were named as threats to movements. Rest, joy, laughter, and pleasure were reframed as political acts rather than indulgences.

The body of the activist as a continuation of the land; scarred but alive. Healing was framed as necessary for sustaining struggle, not as a retreat from it.

Pleasure, consent, and erotic power were discussed as sacred life forces. Naming sexual wounds and reclaiming desire were seen as part of restoring wholeness.

Comrade Rachael Mwikali

11. COMMUNITY, KINSHIP, AND COOPERATIVE HEALING.

Participants imagined new forms of kinship beyond biological family and rigid gender roles. Chosen families, queer lineages, and cooperative models of care were discussed as foundations for African Communities of Healing Praxis.

Ideas emerged around training community healers, forming healing circles, and building solidarity‑based cooperatives for wellness, herbal medicine, and care work.

12. CONCLUSION.

The session closed with the understanding that healing is not an endpoint but an ongoing, widening circle. Healing was affirmed as political, collective, and also as revolutionary

As echoed throughout the day: healed people heal others; healing is survival and healing is liberation.

News, Voices & Impact

Explore updates, field notes, and stories that showcase our mission and impact.