AFRICAN DANCE & COLLECTIVE REFLECTIONS ON HEALING PRAXIS.

Feb 9, 2026

Venue: Mustard Seed, Dandora

Date: 18 December 2025.

Facilitators: Noosim Naimasiah & Marley

Guest Teacher: Faith (African Dance Teacher)

Prepared by: Marwaad Kayse and Enćani Documentation Team

1. INTRODUCTION.

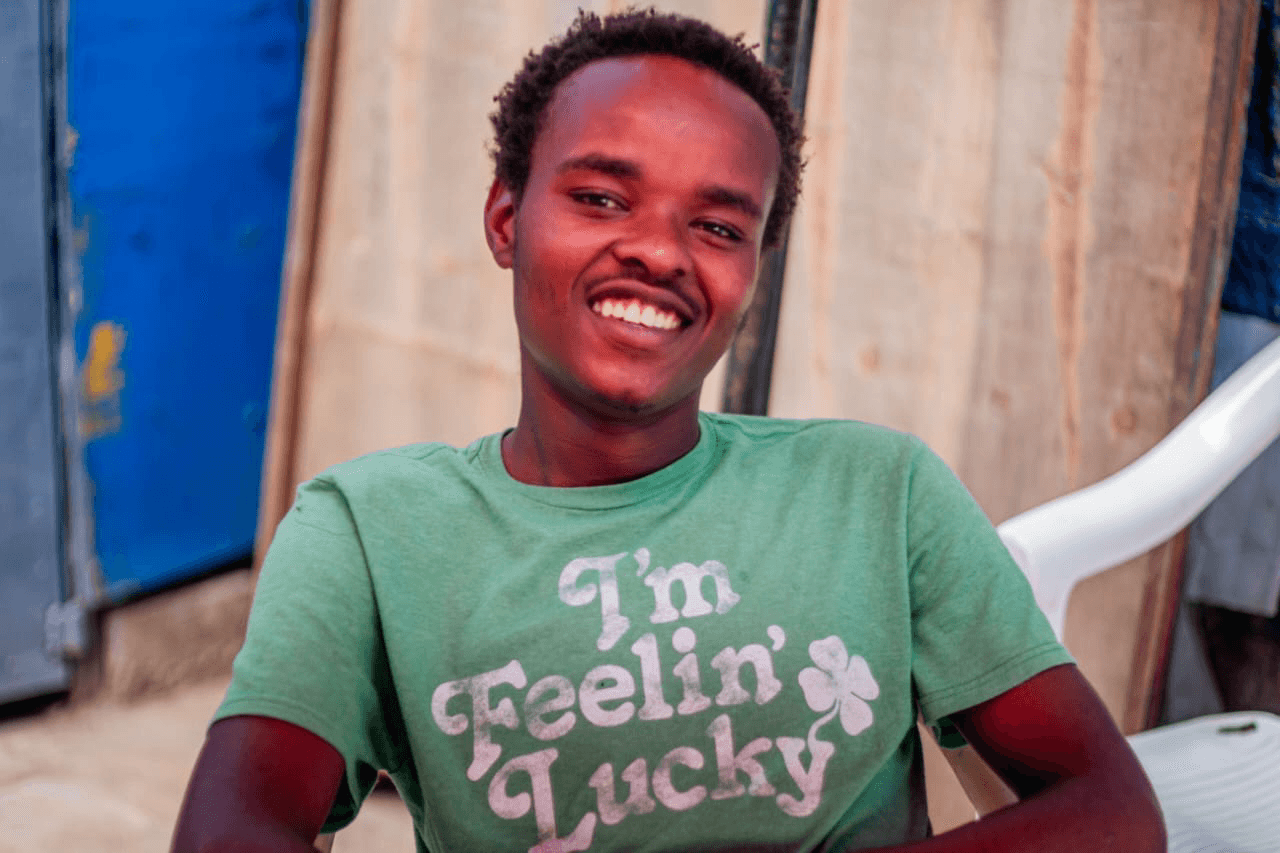

Comrades in a reflective moment.

This report documents African Communities of Healing Praxis (ACoHP) session of 2025 held in Dandora. This report is written from an observational and participatory position. It reflects what unfolded during the day, how the space was held, and how comrades engaged with each other. The objective being to trace and brace each of the comrade’s journey from its trajectory and allowing the healing journey in a collective sense.

2. LOCATION AND ENVIRONMENT.

The session took place in Dandora, Mustard Seed Court. Dandora is widely known as a dumpsite for the city’s waste accounting for majority of the waste in the city. Behind the center, however, is a reclaimed space that was once used for dumping and has since been turned into a park. Zangi a comrade from Mathare, passionate about reclaiming spaces and ecological justice, and Marley showed me around as people continued to arrive. The park includes a playing ground, a football field, and a small garden. This shift from waste to communal use felt significant and shaped the atmosphere of the session.

The venue itself functions as a community space rather than a formal hall. Posters advertising free medical services for youth were taped to the walls. The doors remained open throughout the day. Boys moved in and out of the space, some carrying potted plants to the garden area. On one side, a woman was doing her laundry, possibly because water is accessible at the centre. Marley later shared that comrades from an organisation called Social Justice Travelling Theatre use the space as a base. He also explained that financial reasons influenced the choice of this site, after I asked why this location was selected and how sites are generally chosen for each session. The centre also operates as a theatre and hosts events. After the dancing session, neighbourhood children could be seen watching football nearby.

Mustard seed, Dandora.

3. THE SPACE AS A COMMUNAL SITE.

The space operated as more than just a meeting venue. People came and went freely, children hovered at the edges, and everyday activities continued alongside the session. Laundry was being done, football was being played nearby, and bicycles passed through the neighbourhood more frequently than usual. The atmosphere felt open and communal rather than closed or controlled.

One observation that stood out was Marley’s familiarity with many of the comrades. There was an ease in the way he interacted with others, clapping, joking, and speaking with them in a manner that suggested shared histories and long-standing relationships.

Comrade Marley in a session.

OPENING CIRCLE AND INTRODUCTIONS

The session began with Marley guiding the group as chairs were arranged in a circle. Introductions were exchanged. One participant shared that the community created through these sessions had become a grounding space, explaining that members of the group had supported one another during a funeral. This was shared as an example of solidarity that extends beyond the sessions themselves.

Zangi led chants of “organise, organise, political power,” which echoed through the space. He spoke about the importance of physical gathering, of people being seen and known, and about the uplifting songs being shared, songs about trees, neighbours, and connection to land. He later spoke about recognising systems that oppress both people and nature, expressing caution around false environmental solutions such as carbon taxes and green taxation. The discussion moved fluidly between Kiswahili and English.

After Zangi spoke, Marley asked them to summarise. The group responded with chants of “Viva Zangi.” This practice of saying “viva” followed many contributions throughout the day, often accompanied by words of encouragement.

Ashore followed with the phrase “viva the revolution,” which the group echoed back. They described the space as a haven where people could express themselves freely and be vulnerable. Another comrade added that the space felt like home, with comrades feeling like family. Nyerere spoke about the importance of food sovereignty.

MUSIC, SONGS & COLLECTIVE ENERGY.

Songs continued in a circle. A group of young men, particularly Zangi and three others, were very vocal and energetic, bouncing off one another and acting as hype men. People clapped, moved in rhythm, and repeated chants together. Pan-African songs were shared, and the energy in the space was high. Two women comrades later became more vocal during the singing, A second round of chanting and song followed, so moving that I can only describe it as soldier music sung before battle, led by the photographer. The song was highly energising and carried messages of hope and peace. Statements such as “Tanzania, peace is coming” were shared, offering reassurance and collective optimism. A Swahili song was also sung.

Comrade Nimtez, listening in

Comrade Diana with her daughter, and comrade Faith

FOOD & SHARED MEAL.

A lunch break followed, and there was visible excitement around the food. Noosim spoke and listed the ingredients used in the smoothie (fruits, baobab, soursop. The meal served consisted of sorghum, mushroom sauce, and a side of onions and tomatoes. The food was alkaline, nutritious and comprised of indigenous grains.

Comrades Wachira and Kanare taking the smoothie

Comrades responded positively, with many going myself included going for seconds. Several people, particularly women, asked Noosim questions about the ingredients, where they could be sourced, and how they benefit the body. Faith jokingly told Noosim that if she ate this well every day, Noosim should adopt her on the days she cooked such food. Another participant joked about writing down the recipe for his future wife. Conversations repeatedly returned to food sovereignty, affordability, and access.

DANCE, MOVEMENT & PLAY.

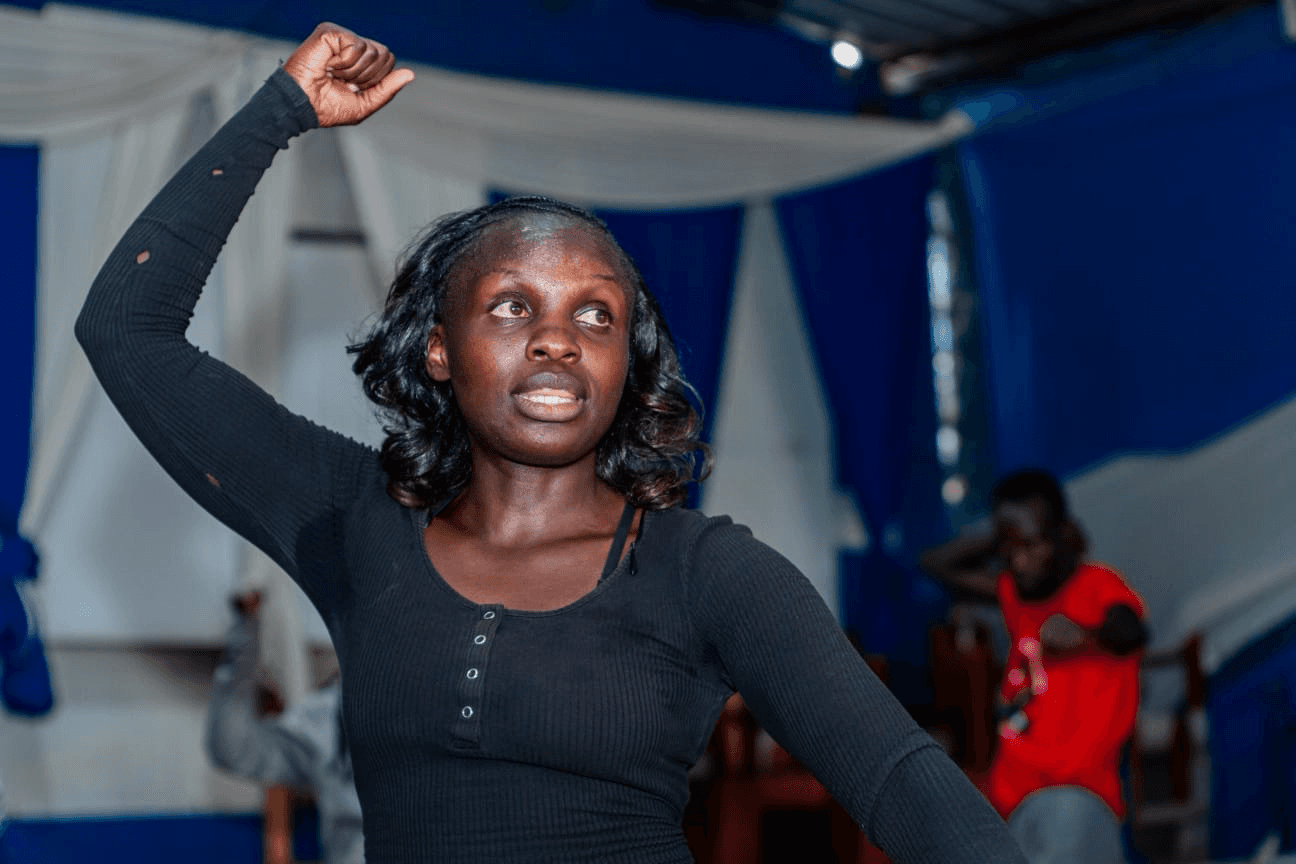

The next session focused on African dance and movement, led by Faith, a dance instructor. This time, music was played from an electronic device, whereas earlier rhythms had been created collectively. The songs had no lyrics, only strong beats, a type of Afrobeat that felt heavy, moving, and warrior-like. Many women appeared to come out of their shells during the dance. Initially, the men stood to one side, but they later became very active. Watching grown men dance freely, with humor and joy, was striking.

Anguka Nayo.

The choreography was taught and practiced in layers. Following a short break, comrades loosely divided themselves by gender, with women on one side and men on the other. After a round of stretching and yoga, we rehearsed the earlier dance once more. Push-ups were jokingly handed out as "punishment" for those struggling to adhere to Faith’s instructions. The room was filled with laughter and the sound of people groaning over the complicated moves, but after a few tries, we finally nailed it.

Comrades sweaty after a dance.

A game involving three colors, red, orange, and pink, followed. Comrades had to jump to the color called out by Faith, and anyone who made a mistake was eliminated. The game generated a lot of laughter and playful frustration. Children from outside came in to watch.

POETRY & CREATIVE EXPRESSION.

Poetry followed the movement sessions. Faith shared a poem about changing the world. Another comrade shared a poem twice, condemning corruption. A piece about the dreams of an African child was shared, followed by a lullaby honoring women in struggle, fighting, organizing, and nurturing.

A Swahili song was also shared, sounding patriotic and collective, though it had been created relatively recently.

‘From Cape to Cairo.’ Comrades in Song.

Another game involved pouring water into a jar. If the water overflowed on someone’s turn, they had to dance in the middle. This activity again drew in neighborhood children. There was teasing, laughter, and playful ribbing as comrades danced as punishment.

PARTICIPANT REFLECTIONS & VOICES.

Comrades later sat in a circle to reflect on previous sessions and the year as a whole. Those who wished to speak raised their hands, greeted comrades, and often ended with chants. Many introduced themselves by name and shared what they do.

Faith spoke about how much she loved the food session. She explained that her family relies heavily on processed food, which is common for many people. She described how vegetables in markets are often washed with sewage water and how the session introduced alternative food practices that were beneficial yet affordable. Herbs were discussed as alternatives to relying solely on formal medical systems. She shared that she had begun connecting directly with farmers for her groceries.

Nimdrod, also known as Nimtez, began with the chant “collective power,” which the group repeated. They spoke about finding companionship and care within the community and emphasized that this feeling deepened with each session. They also expressed appreciation for the food session.

Zangi spoke about ecological justice and land, and about learning more regarding food processes, naming, lineage, and ancestry.

Marley asked comrades about earlier homework that involved retracing family trees and learning the meanings of their names.

Mwana spoke about her work supporting young mothers and addressing gender-based violence. She described the space as one where activists could feel and speak freely, outside of NGO structures. She shared reflections on reclaiming her name and discussing naming within her family, noting how indigenous names have often been erased or replaced. She reflected on being raised in the city without access to farming and how the food session shifted how she thinks about health, energy, and affordability.

Blessing, also known as Moraa, spoke from her experience in cultural centers and theatre spaces. She reflected on tracing the meaning of her name and reconnecting with her family history, including how names were changed following election violence. She also spoke about learning about herbs and shared an experience where traditional medicine helped improve her child’s appetite.

Otieno reflected on identity and naming, and spoke about how the sessions around food and medicine had been meaningful and supportive.

The documentation team in consultation.

10. OBSERVATIONS FROM THE MARGINS.

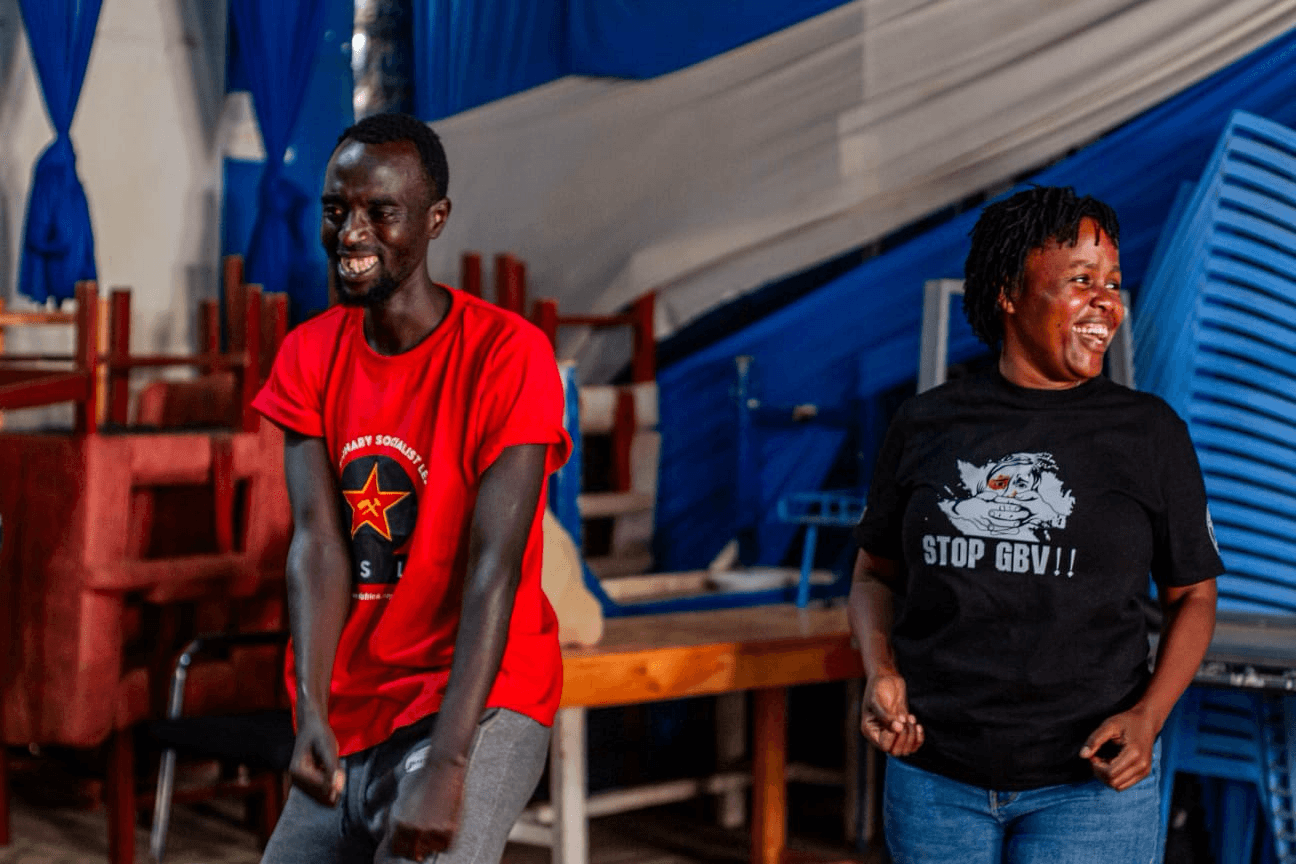

Throughout the day, small details stood out. Young children lingered at the corners of the space, watching quietly. People moved in and out freely. No pre-recorded music was played; rhythm emerged organically through clapping, chanting, and movement. A child played games on a phone nearby. Many comrades wore T-shirts carrying activist messages such as “End Digital Gender Violence,” “Stop GBV,” “Decolonisation Education,” and “Dismantle.”

WIMBO WA MAPAMBANO - Composed by Kang’ara wa Njambi and the Late Karimi Nduthu

Kupigwa na Kupokonywa Maisha Hakutatuzuia sisi Wananchi Kunyakua Uhuru wetu Na haki ya jasho letu... Jasho letu x 2 2. Tumekataa Kupiga Magoti Mbele ya hawa wauaji Bila shaka Sisi pia ni watu Hali ya utumwa tumeikataa... Kata Kata x2 3. Tutanyakua Mashamba yetu Tupiganie Uhuru wetu Tuikomboe elimu yetu Utamaduni na viwanda vyetu... Tukomboe x2 4. Sisi hatutaki kudhulumiwa Hatutaki tena Mauaji Ili Kupe Tuliangushe Haki Na Uhuru Zichanue... Zichanue x2 Uuhuru weetu!!! Kenya, Wakenya ; Uuhuru weetu Wakenya, Tupiganie! Na Haki Zetu! Katiba Yeetu! Mashamba Yeetu! Umoja Weetu!

11. END OF YEAR COLLECTIVE REFLECTIONS.

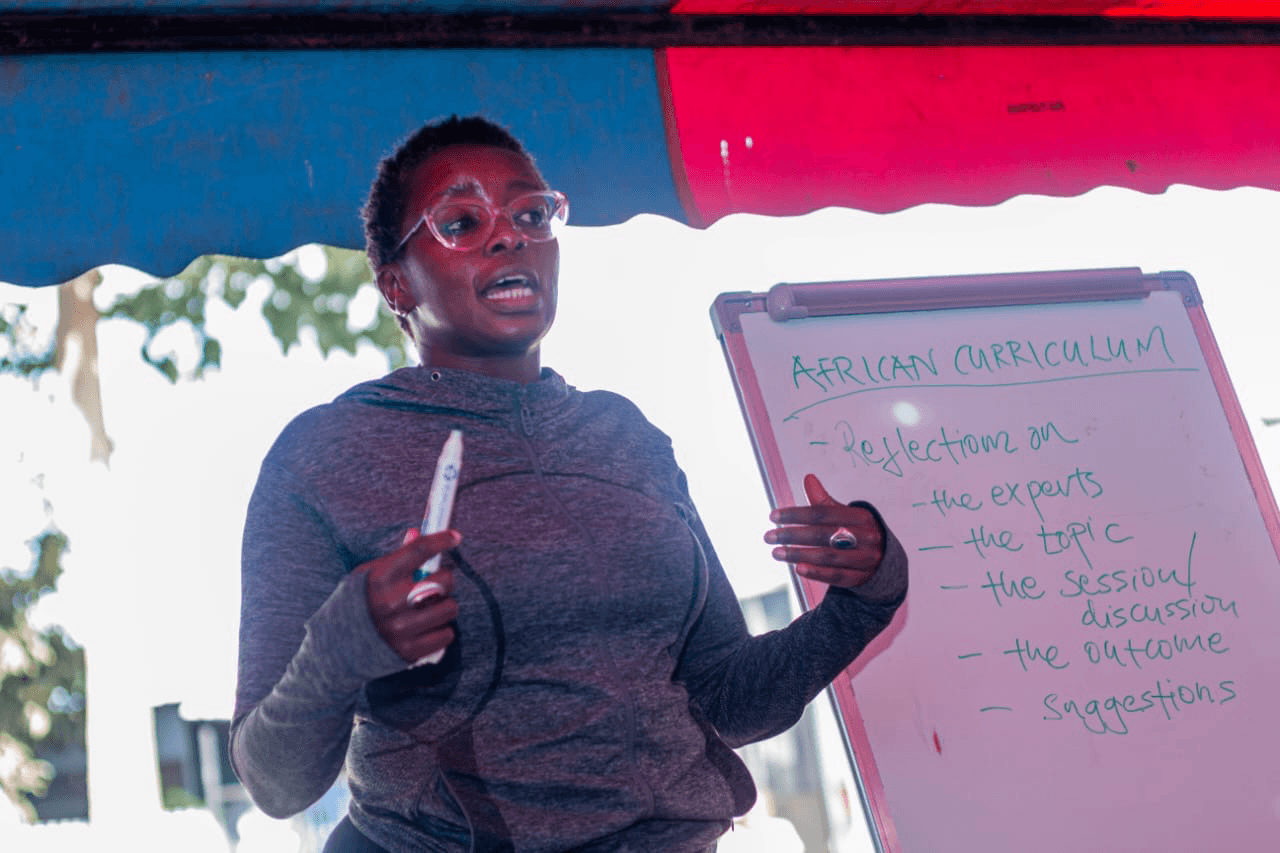

As this was the final session of 2025, a collective reflection was held. Noosim wrote points on the board as comrades shared. Topics raised included the importance of political education for navigating capitalism within African contexts, attendance challenges, substance abuse and relapse, understanding the self, reclaiming African epistemologies, and questioning dominant forms of scientific knowledge rooted in imperial histories.

Comrade Noosim on African Healing Curriculum Program.

Faith reflected that African yoga and dance felt natural and grounding. She suggested that future sessions consider bringing mats, noting that sitting on grass without mats can be uncomfortable for some. Food was again highlighted as a strength of the sessions, alongside the commitment of comrades and the importance of improving timekeeping.

REFLECTIONS.

The reflections shared across this and previous sessions returned again and again to questions of roots, belonging, and what has been lost or interrupted. Naming came up as a powerful entry point. Several participants spoke about how the discussion on names took them back to their roots and forced difficult but necessary conversations within families. There was a sense that many of us do not fully know who we are named after, what our names mean, or the histories they carry. Some reflected on how indigenous names have been erased or replaced, often tied to religion, politics, or moments of violence, and how reclaiming a name can feel like reclaiming self. Tracing family trees was described as both painful and grounding, especially where families are scattered or histories fragmented.

Food emerged as one of the strongest and most repeated themes. Participants spoke about how we have “eaten our roots” and how the food most people rely on today feels empty and lifeless. There was concern about vegetables grown or washed with sewage water, about dependence on processed food, and about how this affects health, energy, and dignity. The food sessions were described as eye-opening, not because they offered expensive solutions, but because they introduced alternative food practices that do not break the bank. Learning about herbs, traditional plants, and indigenous food systems shifted how people think about medicine and healing, with some participants sharing that they had already begun applying this knowledge at home, including directly connecting with farmers and sharing what they learned with their parents.

Land and space were closely tied to these reflections. There was discomfort expressed around how roads, tarmac, and development are built over sacred land, covering graves and histories without consent or care. Dandora itself became part of this reflection, a place known for dumping but also for reclamation, showing both destruction and possibility. Participants spoke about the importance of not renting spaces endlessly, but of reclaiming land and creating spaces that feel like home and family. The idea of reimagining dead or unutilized spaces into civic and communal spaces came up strongly, with this center itself standing as an example.

Knowledge and healing were discussed as collective processes. The space was described as one that brings together people who are well-versed in popular education, lived experience, and community knowledge. There was a shared call to define “our science” and “our knowledge” on our own terms, rather than relying solely on formal or imperial systems. Indigenous knowledge, spirituality, embodied practice, and intergenerational wisdom were all named as central to healing. Practices like African yoga, dance, song, poetry, and dialogue were not seen as add-ons but as necessary ways of reconnecting the body, spirit, and community.

Emotional realities were named openly. Loneliness, depression, fear, grief, and exhaustion were spoken about not as personal failures but as shared conditions shaped by violence, displacement, and oppressive systems. Participants reflected on how comrades often meet only to protest, to respond to crisis or outrage, and how rare it is to meet simply to heal. This space was valued precisely because it allowed people to be vulnerable, to ask questions, to feel, and to be held without judgement. Many described the sessions as freeing, accepting, and energizing, a place where outrage, laughter, fury, and joy could all coexist.

Justice and politics were never far from the reflections. There was a collective recognition that the systems most people are living under were not designed for their well-being. Political education was described as necessary, especially with the coming year expected to be highly political. Participants spoke about the need for people-led and people-guided structures, and about being wary of false solutions, including certain environmental policies that do not address root causes. Justice was framed less around punishment and more around accountability, relationship repair, and collective responsibility.

Looking forward, participants expressed interest in grounding future work in land, food, and cooperation. Ideas such as cooperatives, seed sharing, and bamboo cultivation, were mentioned as possible paths toward ecological justice and economic dignity. There was emphasis on ensuring that indigenous communities are not only included but are central to these processes.

Comrade Zangi in Song.

News, Voices & Impact

Explore updates, field notes, and stories that showcase our mission and impact.